Falling Down as an American Allegory

A not-quite review of the 1993 film.

“How'd that happen? I did everything they told me to. Did you know I build missiles? I helped to protect America. You should be rewarded for that. Instead they give it to the plastic surgeons, y'know, they lied to me.”

— D-Fens, Falling Down

An interesting aspect of revisiting old works of cinema and novels is how perspectives change. This is typical of the human experience in that we look for meaning in these works relevant to the current moment. Recently, I watched the movie “Falling Down” for the first time in decades, coming away with different ideas about what the film represents now.1 Released in 1993, Michael Douglas portrays the character D-Fens, a divorced father and recently fired defense contractor in Los Angeles who has a bad day. One man’s odyssey through a sprawling city where personal encounters with denizens becomes increasingly deranged as his mental acuity deteriorates. Or, at least that was my initial impression of the film as a teenager.

The movie is hard to neatly categorize. It certainly is not an example of the Hero’s Journey, nor the story of an antihero, who, using dubious moral practices, ends up saving the day at the end. No, the main character is in many ways a pitiful creature who reacts to his circumstances in more and more violent outbursts until finally reaching a predictable end.

Yet, he is not altogether an unsympathetic character, and upon rewatching the film in the current year, specific themes relevant to the modern age began to surface.

Three decades later, as numerous memes of the film state, I get the appeal of the film as a metaphor for the state of American society.

The Glorious(?) 1990s

Thinking back where America was in the early 1990s, both culturally and the national mood, broadly speaking, was a very optimistic time. The Berlin Wall fell in 1989 and the USSR, the great nemesis of the 40+ year Cold War, had dissolved not long after. Iraq War 1.0 was deemed a resounding success. Francis Fukuyama’s book ‘End of History’ proclaimed Liberal Democracy as the victor over Communist ideals and political systems.

For all intents and purposes, America was on top. We were the “World’s Only Superpower” as the mantra went.2

The cracks beginning to form in this façade of America’s image of herself were not readily apparent during this time. It would take a series of events that, by themselves small in isolation, added up to signs of things to come in retrospect. Domestic bliss was not the norm. Think of the ATF siege at Waco, Ruby Ridge, the 1992 LA riots occurred as this movie was filmed. While some like to look back to the 1990’s with a halcyon gaze, trouble was brewing below the current papering over with pop culture nostalgia. Though many dreamed up grand ideas of policing the world behind closed doors in US government offices, things on the domestic front were showing signs of strain.

Not long after the release of Falling Down, almost 60% of California voters approved Prop 187 to stem the overflow of illegal immigration to the state. This legislation would, of course, be overturned by the courts later, but the problems continued to grow. Score one more victory for the democratic process, I suppose.

The American Dream™ was already beginning to slip out of the grasp for many during this decade. Other blows would come in the form of economic policies such as NAFTA and corporate offshoring of most manufacture operations. This process didn’t initially start in the 1990s, but began picking up speed in earnest.

[The Critical Drinker’s YouTube video does an excellent breakdown that explores these themes more fully on the socioeconomic backslide.]

As I said at the beginning, this is a not-quite review of the movie. Instead, I have chosen a few scenes to highlight and analyze for what they represent (to me, at least) in the modern age.

Futility of the Times

The movie opens with the protagonist stuck in a typical L.A. traffic jam caused by road construction. Wearing a button-up shirt and tie, pocket protector standing guard for its charge of pens, he sits in a way past its prime economy car which becomes readily apparent when he attempts to turn up the air conditioning, only for it to not work. A fly buzzes around his head, a constant nuisance that he tries to remedy with rolling down a window, discovering that it, too, is broken.

Stuck in the car under an overpass surrounded by others stuck as well, his mind a cacoepy of thoughts, D-Fens can take it no longer and leaves the vehicle, grabbing his briefcase and car keys. Other drivers look on with mild disinterest at this fellow commuter walking away from the fray. One asks D-Fens, “Where are you going?”

“Home,” is the simplistic answer he gives.

While we, the audience, do not yet know that Michael Douglas’s character has been fired from his job as a missile defense contractor(thus no reason to even be in traffic), his frustration at being trapped in a rundown car amongst a sea of humanity resonated as a metaphor of 21st century America.

This miasma of going somewhere and headed nowhere at the same time struck me as a stand-in for where America finds herself in areas of foreign policy and national direction. For most of the 20th century, America had a goal. The 1950s gave us the Space Race, the 1960s till the end of the Cold War was a fight against Communism. Once those things faded into the background America began to drift. Pointless conflicts, cultural squabbles and other insignificant matters took on over-sized importance in the national mind.

The question of who we are and where we are going remains.

Economic Volatility

Leaving his vehicle, the first encounter he has is with a Korean store owner that he asks for change to use a payphone. Told brusquely that to get change he will have to buy something, D-Fens selects a Coca-Cola, only to find out that the high price for the soda doesn’t leave him enough change to use the payphone. This leads to a rant about “Rolling prices back to 1965” and a lot of property damage as he walks around, asking what the costs for other goods in the store are— before smashing them to bits.

Most Liberal interpretations of this scene tend to lean on old racial tropes that D-Fens simply has prejudice for the Korean storekeeper, but I disagree with this analysis as lazy. A later scene at his mother’s home displays pictures of his father in uniform during WWII, and it’s plain to see he is a life-long Angeleno that is no stranger to seeing a diverse group of people in the mega-city. No, his anger is directed at the economic commodification of society where everything seems to be maximized for the most profit. As an aside, it was comical to see him bewildered at the $0.85 price of the soda when comparing today’s cost.

Empire of Dust

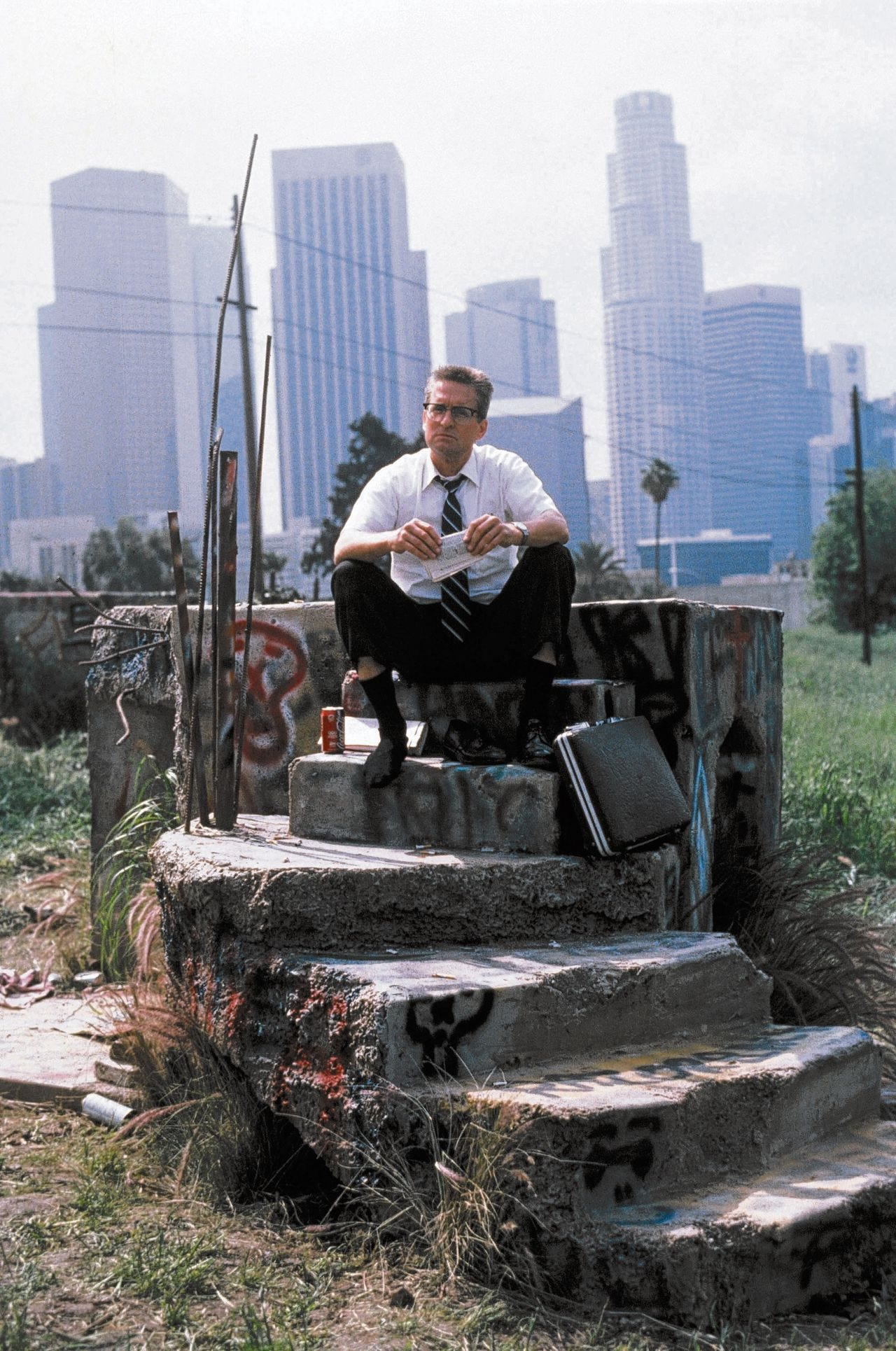

After the confrontation in the convenience store, D-Fens goes to a derelict, rundown public park with graffiti-laden structures. As he sits atop one of the crumbling piles of concrete, the scene contrasts Los Angeles skyscrapers in the background — highlighting the close proximity of difference in class and living standards.

He is accosted by gang members who tell him that he is trespassing in “their” territory, pointing to the graffiti tags as proof. D-Fens attempts to defuse the situation and simply leave, but they demand he pay a toll for the offense of intruding on their turf. They demand that he hand over his briefcase.

He refuses and successfully fights them off with a baseball bat he had acquired from the convenience store earlier.

Rule of Law follows the tenets of Calvinball

Arriving at a fast food joint named Whammyburger, he tries to order breakfast but is told that they stopped serving at 11:30. Glancing at his watch, it’s past that time by only a few minutes. There are even boxes of breakfast item sitting behind the counter girl. Things… go downhill from this point is all that I will say. This scene (and the movie) deserves a viewing, even if one only watches the clip on YouTube.

This situation of a rigid adherence to a nonsensical rule is an excellent example of Anarcho-Tyranny, especially in light of the previous scenes where lawlessness and gang held territory is the norm, yet the simple act of providing a breakfast sandwich shortly after the allotted time is considered impossible.

Duality

“We're the same, you and me. We're the same, don't you see?”

“We are not the same. I'm an American, you're a sick asshole.”

D-Fens visits a military surplus store looking to get a pair of boots to replace his worn out shoes. The owner3 hides him from the police who are aware of his trail of madness across LA. His reason for doing so become apparent as he’s been listening on a police scanner and knows who D-Fens is. This creates a quasi-kinship as he believes all these actions are part of a vigilante spree.

D-Fens is disgusted by this, as he views his actions as a righteous response to the conditions around him. This angers the owner as his illusions about D-Fens motivations evaporate.

Veneer of Success

On his walking odyssey through Los Angeles, D-Fens passes through MacArthur Park. (yes, that MacArthur Park) It is filled with homeless, drug addicts, and others who have fallen down in society. A man accosts D-Fens, asking for money and claiming to be a veteran of the Vietnam War, even though it is obvious that he is too young to have been in the conflict. D-Fens sees through his lies, but end up giving him the briefcase he’s carried all this time.

Upon opening it, we the audience see that it is empty, except for a small lunch packed for the workday at a job he no longer has. Even with everything going on, this showed how keeping up a false appearance of normality and success was important to D-Fens.

Corruption as Coin of the Realm

A running theme throughout the film is how the protagonist constantly faces an endless series of construction projects that impede his journey. While earlier scenes have him forced to navigate around these obstructions, towards the end he is done with the excuses. He demands the worker tell him the truth, that the construction is unwarranted and simply a boondoggle project to justify their budget. Seeing his firearm, the worker admits that yes, it is unnecessary work and only being done for that purpose.

In modern times, not a day seems to go by without another grift or scam being uncovered in the news. It has become a ubiquitous part of the social fabric that this is merely something we’re supposed to expect now.4

Desperation and Finality

“Is that what this is about? You're angry because you got lied to? Is that why my chicken dinner is drying out in the oven? Hey, they lie to everyone. They lie to the fish. But that doesn't give you any special right to do what you did today.”

Falling Down is not a blueprint for actions someone should want to emulate in real life, obviously. However, for a film that came out over three decades ago, its themes of frustration and disgust with how society operates has relevance for today. D-Fens meets his end, but between the brutality and violence, the questions he poses on the rot and decline of the nation still deserve answers.

-Arthur

If you enjoyed this essay, please share it, or you can buy me a coffee in appreciation.

As I wrote, perspectives on works of fiction can wildly differ. Here’s an article that sees no redeeming qualities or themes from the movie and simply chalks it all up to the usual fare of toxic masculinity, White fragility, and revenge fantasy. Hey, White People: Michael Douglas Is the Villain, Not the Victim, in Falling Down

That this implication meant we were determined to also be the world’s policeman was not fully understood by the greater American public at this time.

This Hollywood trope of putting in an over-the-top racist neo-nazi character is jarring for a movie set in 1990s Los Angeles. But it gives folks a chance to compare him and the D-Fens character to conservatives, so I guess that’s its purpose. Here's the two types of Trump supporters in a nutshell.

Yes, corruption is not something new. I remember reading the “That’s Outrageous!” section of Reader’s Digest as a teen listing the latest scandals coming out of DC. But there is a distinct vibe of it being accepted as a norm these days, and not shocking at all when uncovered.

Well put together article you've birthed here Arthur.

A lot to grasp at to discuss, but one that I want to call attention to is the allegory of the construction sites to our own reforging (whether willingly or not) of traditional American values: gender as a spectrum, entitlement, open borders, and the ever present slow lurch toward collectivism; the old schools be damned.

I don't think all of us are at the point of abandoning all hope, but many have; admittedly I'm holding on to any stable footing I can find.

Great read!

Saw this when it came out. Like your treatment. I'll have to watch it again. Thanks!